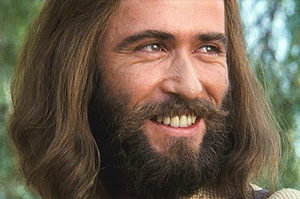

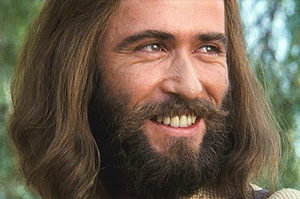

Jesus in the Quran

JESUS in the Quran JESUS IN THE KORAN AND INTER-RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE After much reflection, I have decided, for the first editorial of this blog, part

Let us imagine two North African countries. One is a fledgling democracy with a bright future. It boasts a social safety net superior to that of its neighbors and strives to provide free health care to its citizens. The country has a modern highway, port and airport infrastructure. It has the most modern highway, port and airport infrastructure in Africa, and is the leading railroad country in Africa. The country has succeeded in establishing itself firmly in advanced industrial sectors such as aeronautics*(2) and automobiles*(3).

The country has completed other major projects in just a few years, thus demonstrating its ability to effectively and rapidly realize its long-term strategic ambitions, mainly in agriculture, renewable energies*(4), tourism (13 million tourists in 2020), fishing, electronics, services, mining, mainly phosphate, cobalt, lithium, zinc, copper, etc…

The press is relatively free, and the political system is open: opposing parties compete bitterly in elections, but peacefully succeed each other in power. It has escaped the wave of military coups that turned the neighboring country into a dictatorship.

Thanks to a long-standing political alliance and privileged economic relations with the countries of the European Community and the United States in particular, and thanks to its continued influence and its new image as a major player in Africa, in addition to its distinguished position in large-scale partnerships, have caused its neighbor to experience a “political breakdown”, which is at the origin of the moral decadence in which the leaders of this country are entangled.

This country has become in a few years the 2nd investor of the African continent after South Africa (6.8 billion DH in 2019). Thanks to the extent of the breakthroughs that this country has achieved in recent years, it has managed to become a crossroads of dialogue and cooperation and a strategic actor of exchange between the countries of the North and the South. It is still a developing country, but it is among the leaders.

The economic actors have allowed this country to show some resilience in the face of the challenges imposed by a very turbulent global context.

The country has experienced a mixture of destructive policies, authoritarianism and kleptocracy, under the influence of a certain Marxist ideology that came mainly from Moscow.

The causes of the country’s bankruptcy are profound. Decades of gradual economic decline, a corrupt autocracy at all levels, mainly in the military nomenclature…

The exceptional economic growth of this country in the 1970s was only a memory. The “advances” noted during this period hid a malaise, a fragility and great threats. With a premonitory formula, a German diplomat estimated at the time that this euphoria resembled “a dance on a volcano”. History will prove him right.

In the 1980s, the drop in oil revenues led to an unprecedented economic slump, a drop in public spending, cuts in social programs, an increase in unemployment and unbearable hardships for the poorest, etc…

In compensation for the confiscation of national sovereignty by the executive since 1962, the Treasury of this country subsidized everything: flour, semolina, oil, sugar, fuel, water, gas, electricity, employment, investment, public enterprises, the newspaper, etc. In total, the bill amounted to about 20 billion dollars per year When hydrocarbon export revenues reached $77 billion as in 2009, the burden was bearable. By 2020, just $23 billion in hydrocarbon export revenues. And it didn’t get any better. With Covid, tax revenues have been drastically reduced and public spending has increased, while domestic consumption has soared (+8% per year).

The end of the free-for-all distribution of public money sooner than expected is inevitable. The march towards the abyss and the bankruptcy of the regime of this country are started and become inevitable.

In order not to be caught off guard, the generals have successively put in place an impressive repressive regime. Almost sixty years of terror! And the management of terror is surely the only “serious” and really “thoughtful” political program that the regime has been able to put in place to solve its own existential anguish: how to take power without ever giving it back? The crime of the state preceded the state. Political assassination is an old and formidable weapon of war that the power of this country has perfected since independence and even before. It has cultivated it to the point of making it its main response to political adversity and all forms of opposition, intellectual dissent or social protest.

The physical liquidation, the torture, the humiliation of the being and all the other processes of enslavement, extremely sophisticated, are the characteristic references of a military regime that, after sixty long years of an absolutist oligarchy, sixty years of total chaos, still refuses to give up, in spite of the democratic demands of the society.

During the period of the struggle for Algerian independence, entire regiments of the Moroccan liberation army refused to lay down their arms so as not to abandon the Algerian FLN, left to its own devices on the ground, and supported their brothers body and soul in the Saharan confines, particularly in the region of the high plateaus and Figuig.

The FLN leaders of the time transformed their operational command posts of the border army in Oujda into a real headquarters, with an administration, its specialized services, its schools of executives, its hierarchy of officers and non-commissioned officers.

In 1960, the Algerian border army in Morocco had about 8,000 men to fight the French army.

A truly unknown episode in the history of Algerian independence, the revolutionary movement and the post-independence period in Morocco. In the early 1958s, Trotskyite militants ran secret factories in Morocco on behalf of the FLN. Workshops of manufacture of weapons were born in Tétouan, in 1958 (manufacture of grenades), in Témara, in 1960 (manufacture of PM MAT 49 and white weapons), in Souk-El-Arba, in 1958 (manufacture of bombs, grenades, torpedo Bangalore), in Skhirat, in 1960 (manufacture of mortars of 45 and explosives), in Bouznika, in 1959 (manufacture of bombs, grenades and white weapons), and Mohammadia, in 1960 (manufacture of mortars of 45, 60 and 80). In Témara alone, more than 10,000 machine guns were manufactured, tested and sent to Algerian fighters.

After his return from exile and after the independence of Morocco, Mohammed V made his famous speech to his people to show compassion and solidarity towards his brother the Algerian people. And it was quite normal because we Moroccans were educated in solidarity, sharing, generosity and the dream of building, tomorrow, a great Maghreb that would recall the “golden age” of Andalusia. Our destinies were organically linked, they still are and they will remain so. The two peoples know and complement each other. They have always been deeply intertwined and interdependent, so much so that one may wonder about the limits of the effective line of separation between the two countries. The brotherhood that binds the two peoples is very deep and no political will can alter it.

The two peoples have, for an eternity, lived with serenity, quietude and compassion their Arabness, their Amazighness, their Africanness and their "Mediterraneanness". These four values of their identity, which are steeped in history and inspired by the cardinal values of both countries in terms of openness, diversity and sharing, must be fully assumed. This is how they can be mutually enriched by these four common spaces because their economic, cultural, social and spiritual enrichment depends on it. It is in this way that we could become true Maghrebians at heart: we are all Algerians, Tunisians, Moroccans, Mauritanians, and Libyans...

When Algeria regained its independence in 1962, all of Morocco was in celebration and jubilation, a memorable memory. Moroccans were full of hope for the success of the construction of this great Maghreb.

After independence, Morocco naturally chose NATO given the history that linked it with the United States, especially after the landing of American forces on November 8, 1942 in Casablanca, Safi and Mehdia and the Anfa conference that took place from January 14 to 24, 1943 and which brought together, in addition to the late Mohammed V, the American president Franklin Roosevelt, the British prime minister Winston Churchill and General de Gaule. This conference was decisive both for the outcome of the greatest armed conflict of modern times and for Morocco’s aspirations to regain its independence.

On the Algerian side, it was in the geopolitical logic of this country to take the Marxist software because this software was the basis of the Algerian independence movement.

This obviously created a political split between the two countries. But unlike Morocco, Algeria, for lack of vision, has maintained the cold war software that has remained dominant to this day within the Algerian regime. Algeria believes that life is a permanent war because in war, all blows are allowed and it is always easier to assume one’s aggressiveness when one starts from the principle that the other belongs to a clan that must be destroyed.

In need of a reference point, the Algerian regime has gone from a state of debauchery and intellectual sloppiness to a state of moral decadence, cultivating an exacerbated grudge against Morocco. History does not change geography, while geography, in its essence, “plays a role in history. It is therefore clear that Algerian actions disregard all considerations and have no regard for either history or geography.

The dishonesty, the bad faith, the denial, the lies of the Algerian regime are strategies that respond to a need for reference to identify oneself, to define oneself with others and with oneself. It is the need to confer legitimacy on itself in order to continue to exist without having to face disturbing questions, those that would push it to question itself, those that threaten to shake its belief system, to shake what it has spent decades building and consolidating to finally see it collapse like a house of cards.

When Algerian dictators argue with zeal, aggressiveness and offensiveness, it is not the other that they are trying to convince first, but themselves. They want to convince themselves that they are right. That’s why they need to justify themselves, to convince themselves that they are right. Of course it is an illusion, but it is a need to prove themselves right.

They do not place themselves at all in a dialectic of truth, they do not place themselves in a perspective of investigation of the truth, they are not interested by the bottom of things, they prefer praise to truth, success to wisdom, obstinacy to understanding, to benevolence and understanding. They place themselves in a heuristic dialectic, i.e. in the art of controversy. They are not part of a Socratic approach of the dialectic of truth.

Lorsque Socrate disait:

"Tout ce que je sais c’est que je ne connais rien"

il voulait dire que La reconnaissance de notre ignorance est l’attitude nécessaire à adopter face à la quête de la vérité. L’ignorant prend ses croyances et ses convictions pour la réalité et méconnait son ignorance. Il est persuadé de connaître tout et de ce fait, il abandonne toute posture de recherche et n’essaie plus à connaître puisqu’il croit tout savoir !Socrates Tweet

One could compare the beliefs of the Algerian regime to a building that would threaten to collapse if one floor were removed. This regime spends its whole life building a system of belief and assumption, a superstitious system in the absence of any true facts. Once this system is built, it is out of the question to question it. So this regime always prefers to patch up the cracks, to build scaffolding to try to convince itself that its system is the best. In any case, it is out of the question to let its edifice, its beliefs be destroyed because without this belief system, it becomes vulnerable, it is in danger. This is why he is always at war with the other side. He refuses to recognize the value of the arguments of the opposite side. He considers that any idea emanating from this clan is necessarily null and void. It is the logic of the militancy which does not think because to think is to give oneself the occasion to change opinion and thus to be in the discomfort even the psychic insecurity, it is thus to see appearing a crack in the edifice of its beliefs. It is a fight of ego, a fight for survival.

Those who hold the power in Algeria since the independence used stratagems, ruses, feints, warlike maneuvers, artificial means, fallacious arguments to make triumph their conception of the truth, their beliefs.

All this informs about the exhaustion of the reigning thought in Algeria, this agonizing thought on the verge of clinical death. This also explains the frenzy and the exacerbated resentment towards Morocco.

On December 8, 1975, while the Muslims were celebrating one of the most important feasts of their cult: the Feast of the Sacrifice (Aïd El Kébir), the Algerian government took the decision to expel 350,000 Moroccan citizens who had been legally established on Algerian territory. These people who have been integrated for decades in Algeria, have founded families (especially Algerian-Moroccan), have taken up arms during the war against the French occupier, are being expelled, arbitrarily and without warning, to Morocco. An immeasurable pain, all the more acute because the exaction was committed by the officials of a neighboring country, a brother country.

And again, a real mini-remake of the 1975 expulsion happened on March 18, 2021, when Moroccan farmers were brutally expelled from their lands in El Arja. An area of about 50,000 fallow palm trees and 30,000 planted over decades, which produce one of the most coveted date species on the international markets, is despoiled by the Algerian army.

As Mohamed Berrada*(5) has pointed out, Algerian “thought” has shrunk to the point where it is no longer capable of persisting in its opposition to Morocco by showing a minimum of respect for the moral rules of political conflict, including those of war and armed conflict. The question arises now as to the direction that this Algerian political and media “thought” is taking in the wake of the abject behavior of the private TV channel Echourouk News, which is an attack on the most important symbol of Moroccan sovereignty and the pillar of the Kingdom’s constants.

This TV channel, very close to military circles, has caricatured King Mohammed VI in a satirical program where the sovereign was parodied as a puppet. This unflattering image of the King simply does not concern us. The journalists of this channel have the right to play pee-pee, but their childishness, their representations do not concern us. I would like to base myself on a wise interpretation that we discovered in the 20th century to quote an excellent Belgian surrealist painter that I love very much, René Magritte, who had already posed the problem of representation with his very famous star that represents a pipe, accompanied by the following legend: “This is not a pipe”. This painting has become one of the most emblematic artistic works in the world, even painted in the most realistic way, a pipe represented in this painting is not a pipe. It remains only an image of a pipe that cannot be stuffed or smoked, as would a real pipe. Indeed, an image is never the object “in itself”, but a representation subject to interpretation. The debate boils down to this. Your caricature does not represent our King in any way. Period.

This reminds me strangely of this anecdote told by Gérard Haddad*(6) about his dog. Nemo, the dog's name, is fascinated by the smallest reflective surface, the store windows and the elevator mirror. He plants himself in front of it, motionless, in an attack position, before throwing himself violently on the reflecting surface in a kind of imaginary joust where he must surely hurt himself by bumping into the wall. He seems to hate this stranger, he fights with him. He wants to forbid him the access to his space, to his home. He barks with rage. This reminds me strangely of the Algerian men of power, civil or military, who suffer from the same serious handicap. The mirror which, in general, allows the child to discover himself for the first time, to appropriate his identity and to gradually shape his autonomy with joy and happiness, the mirror becomes rebellious and ambiguous for the Algerian men of power. Far from rejoicing, they live these moments as a heartbreak. Before the cape of the "mirror", they possess an unconscious and imaginary image. After, they undergo a traumatic shock. The dream mirror becomes a broken mirror that reflects distorted and damaged facets that prevent them from identifying their own image. The broken mirror has plunged them into a world of apparitions and ghosts and has led them to madness as in the myth of Medusa where the gaze of the other is that of death.

This is how the Algerian men of power adopt the same reflex as the dog Nemo. That is to say, they don’t even recognize these humans they meet as their fellow human beings, but as repulsive beings, mortal enemies that must be kept at a distance, and the ideal would be to destroy them and even kill them. A dog’s rage.

Why so much snarling at the highest level of the Republic of Algiers; so much systematically derogatory media harassment; so much assiduity in wanting to inculcate a real culture of hatred between the two peoples? Why this incredible expenditure of energy and means, in all the forums of international diplomacy, just to impede the legitimate will of Morocco to complete and preserve its territorial integrity? It is true that Morocco annoys Algeria at the highest level. What better way to break this momentum than to push the Sahara issue to the point of intolerability. The famous principle of the “right of peoples to self-determination” is only a prop that was shattered when Abdelaziz Bouteflika proposed, in 2002, the division of the former Spanish colony by giving Algeria the southern part, evacuated by Mauritania in 1979, as Youssef Chmirou*(7) has rightly pointed out

Hadari, hadari. Dictators often end up being hanged, shot or tried and imprisoned. Without mentioning mythical personalities such as Mussolini and Hitler, the images of some Arab dictators are in everyone’s mind. Those of Saddam Hussein, who came out of the hole where he had been hiding and then led to the gallows on December 30th 2006. Those, too, of Muammar Gaddafi captured in the street near Sirte, raped before being put to death on October 20, 2011. The popular vindication is a formidable instrument of justice that is characterized by a succession of acts of barbarism, human treatment that can be cruel as the beating, tying, lynching, etc..

Hundreds of thousands of Algerians still feel frustrated, betrayed, disillusioned, abused and disoriented in the face of a regime that has silenced all discordant voices and plunged into despair a people caught between a standard of living at half-mast and an impressive repressive regime.

Algerians are protesting. They intend to fight for their rights and their future. As hopeless as the prospects seem, this tradition of revolt could lay the foundation for a democratic restoration. It won’t be easy, nor will it be quick. But rebuilding a state on the verge of bankruptcy has never been easy, says Abdellah Tourabi*(8)

In the meantime, what can we hope for in Algeria? No doubt that Algeria will experience the happiness of a Moroccan-style changeover, and that our best enemy, Comrade Tebboune, will be succeeded by a strong man, capable of bringing together clans, calming conflicts, guiding the country along a path of harmony and brotherhood, and creating the foundations of a true democracy and a space of peace, prosperity, sharing, complementarity, partnership and mutual respect in a united, supportive, civic-minded and benevolent Maghreb

It is high time for the Algerian people to get rid once and for all of their obstacles: military regimes and Islamism. Millions of Algerians dream of a menu other than these two indigestible dishes.

Jalal Boubker Bennani

JESUS in the Quran JESUS IN THE KORAN AND INTER-RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE After much reflection, I have decided, for the first editorial of this blog, part

Christianity in Morocco A BRIEF HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF CHRISTIANS IN MOROCCO We are going to fly over a few periods of the very ancient and

“Like tolerance, philosophy is an art of living together, respecting common rights and values. It is a capacity to see the world through a critical

The first « think tank » unique in the world: an interfaith Woodstock THE MONASTERY OF TOUMLILINE In a world in “perpetual” distress, desolation, drift,

REINVENTING TOUMLILINE “A people without memory is a people without a future” wrote Aimé César or “He who does not know where he comes from

Test042024